LII

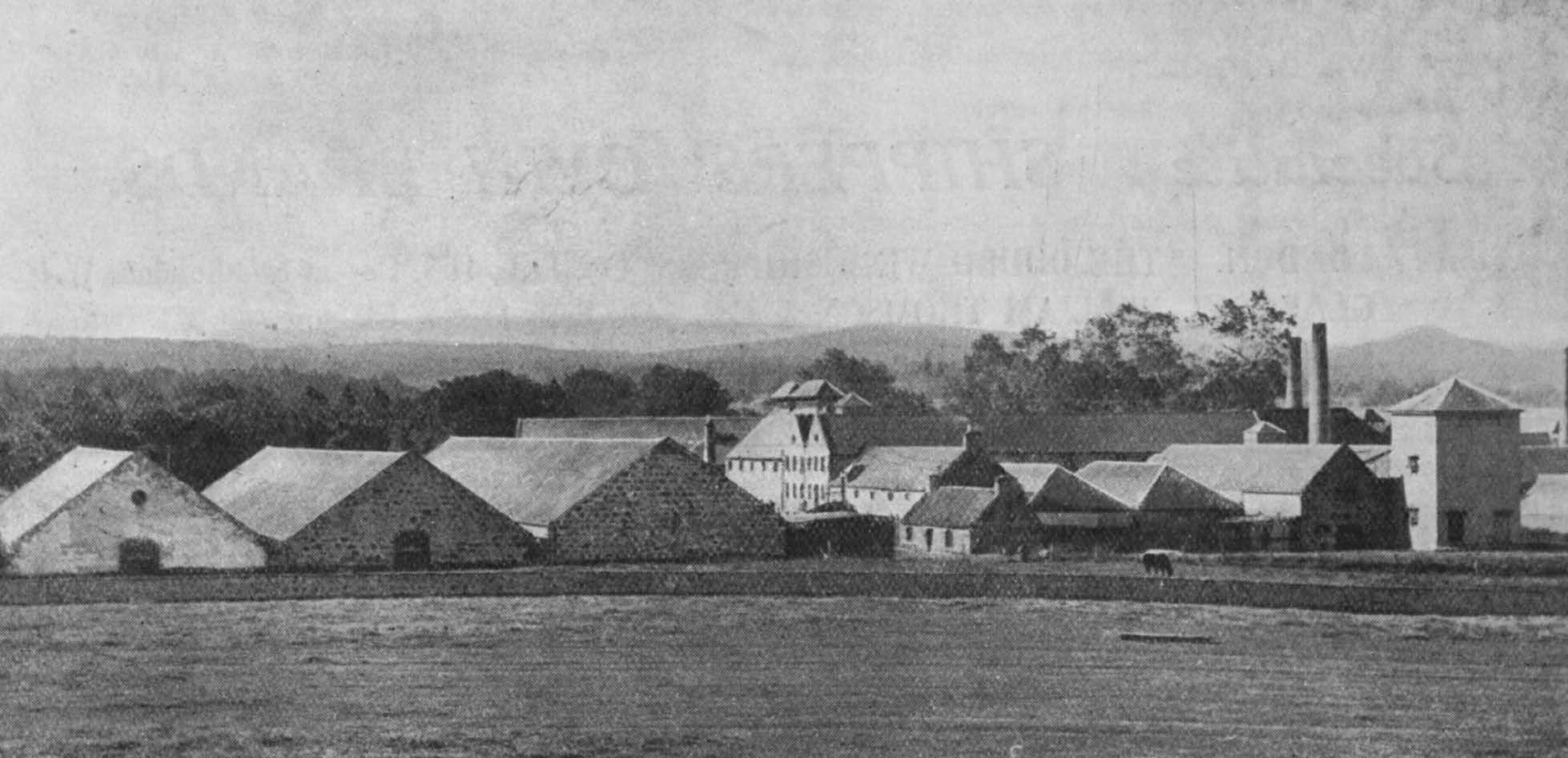

Royal Brackla Distillery, Nairn.

July 14th, 1924

The Royal Brackla Distillery lies some four miles from the ancient Royal Burgh of Nairn, in a picturesque part of the country, made famous by Shakespeare in the tragedy of “Macbeth.” Through the premises runs the Cawdor Burn, and nearby is Cawdor Castle, where Shakespeare, with his casual disregard of anachronism, laid the scene of the murder of King Duncan by the usurper Macbeth, although the event actually took place four centuries before the castle was built, in the year 1454, by Thane William! After the battle of Culloden, Simon, Lord Lovat, hid for several days in an attic on the roof of the tower of Cawdor Castle.

Records of the Royal Burgh of Nairn date back to the thirteen century, when the town was called “Invernairne.” The castle, of which practically nothing remains, was one of twenty-three surrendered during the reign of Edward I., when Bruce and Baliol quarrelled over the crown of Scotland. Later, in the war which preceded the recognition of the independence of the country, the castle was demolished by Robert Bruce. A charter granted by James I. relates that the burgesses of Nairn “in all times past, beyond the memory of all whomsoever, were in use and possession of having an electing a provost and baillies, holding courts, administering justice, creating burgesses, selling Wine, wax, wool, cloth, fish, flesh, and other merchandise and victual, and holding and having workmen, of whatsoever kind, and also power of electing representative to Parliament, of levying customs, anchorage, and harbour dues on vessels using the harbour of the burgh, commonly reputed to the same.”

Modern Nairn, beautifully situated on the shores of the Moray Firth, is a well-known Scottish holiday resort. Fishing, with which more than a quarter of the population is directly or indirectly connected, forms the chief local industry. The fishermen live in the corner of the town without frequent association with the remainder of the inhabitants. They are proud of their pedigree as a separate community, and have almost one name in common – Main. There are, for instance, between twenty and thirty “John Mains,” and for purposes of identification a third name is added, so that one hears of John Main “Ellen,” John Main “Baillie,” and John Main “Jamieson.”

Not far from Nairn is Fort George, now the depot of the Seaforth Highlanders, and formerly one of the chain of forts designed to overawe the Highlanders after the ’45. It was constructed in the year 1748, and at the time was said to be the most complete military fortress in Great Britain. Laid out on the principles of the great engineer Vauban, it mounted sixty guns, several mortars, and had bomb-proof accommodation for nearly three thousand barrels of gunpowder. During their Highland tour Dr. Johnson and Boswell were the guests of the Governor on one occasion, and so excellent was the dinner, and the band which played in the courtyard, that the great man remarked: “I shall always remember this fort with gratitude.” The cost of building Fort George, a work occupying several years, severely taxed the resources of the Treasury, and King George II. is said to have expressed his annoyance at the repeated demands for money by remarking petulantly: “Surely to God its streets are paved with gold!”

The Royal Brackla Distillery is one of the oldest in Scotland. It was built in the year 1812 by Captain William Fraser, at a time when lawful distillers laboured under great difficulties. Within a specified Highland area a duty of £1 4s. per annum was imposed upon each gallon of the still’s content, the Excise authorities assuming that a still at work would yield a certain annual produce for each gallon of its capacity. It was calculated that so much time would be required to work off a charge, and the officers merely visited the distilleries from time to time to see whether additional stills were in operation or if larger vessels had been substituted for those already gauged. Consequently the distillers soon contrived means of improving the construction of their stills, so that, instead of a week being required to work off a charge, the process could be carried through in twenty-four hours, later in five or six hours, and finally in the brief space of eight minutes. So far were these improvements advanced that a still of eighty gallons’ capacity could be worked off, emptied, and ready for another operation in three and a-half minutes. A still of forty gallons could be drawn off in a two and a-half minutes, until the amount of fuel consumed and consequent wear and tear made the distillers’ gain a matter of doubt. To meet these clever practices on the part of distillers, duty was increased year after year. In 1814 it amounted to £7 16s. 0¼d. per gallon of the still’s content and 6s. 7½d., two-thirds additional on every gallon made. With this method of charging duty distillers found their interest lay in increasing the quantity of their make at the expense of smuggling. The Government finally decided to prohibit the use of stills of less than 500 gallons’ capacity. That such legislation was unsound is shown in the following explanation written by an authority at the time. “By Act of Parliament,” says the writer, “the Highland district was marked out by a definite line, extending along the southern base of the Grampians, within which all distillation of Spirits was prohibited from stills of less than 500 gallons. It is evident that this law was a complete interdict, as a still of this magnitude would consume more than the disposable grain in the most extensive county within this newly-drawn boundary; nor could fuel be obtained for such an establishment without an expense which the commodity could not possibly bear. The sale, too, of the Spirits produced was circumscribed within the same line, and thus the market which alone could have supported the manufacture was cut off.” For these and other reasons there was scarcely any alternative but recourse to illicit distillation, for taxes were as absurdly high as they are to-day, and one can only wonder that legitimate distilleries such as Royal Brackla paid their way in these stormy times.

The water used at the distillery is drawn from springs high up amongst the Cawdor Hills, and the barley used is practically all grown in the counties of Moray and Nairn, the proprietors holding strongly to the opinion that real Scots Highland Malt Whisky can only be produced with the native products, water, barley – and brains.

Two Sentinel steam wagons are used to convey supplies to and from Nairn station. An elevator hoists the grain in the usual manner to a capacious barley loft, where it is steeped in two steeps of 50 quarters’ capacity. There are three germinating floors, a kiln of 75 quarters’ capacity floored with perforated plates, and grinding is done by means of a two-roller mill of the old type. Such old-fashioned mills are generally referred to with respect where they are used, and the machine at Brackla can grind 400 bushels in little over an hour.

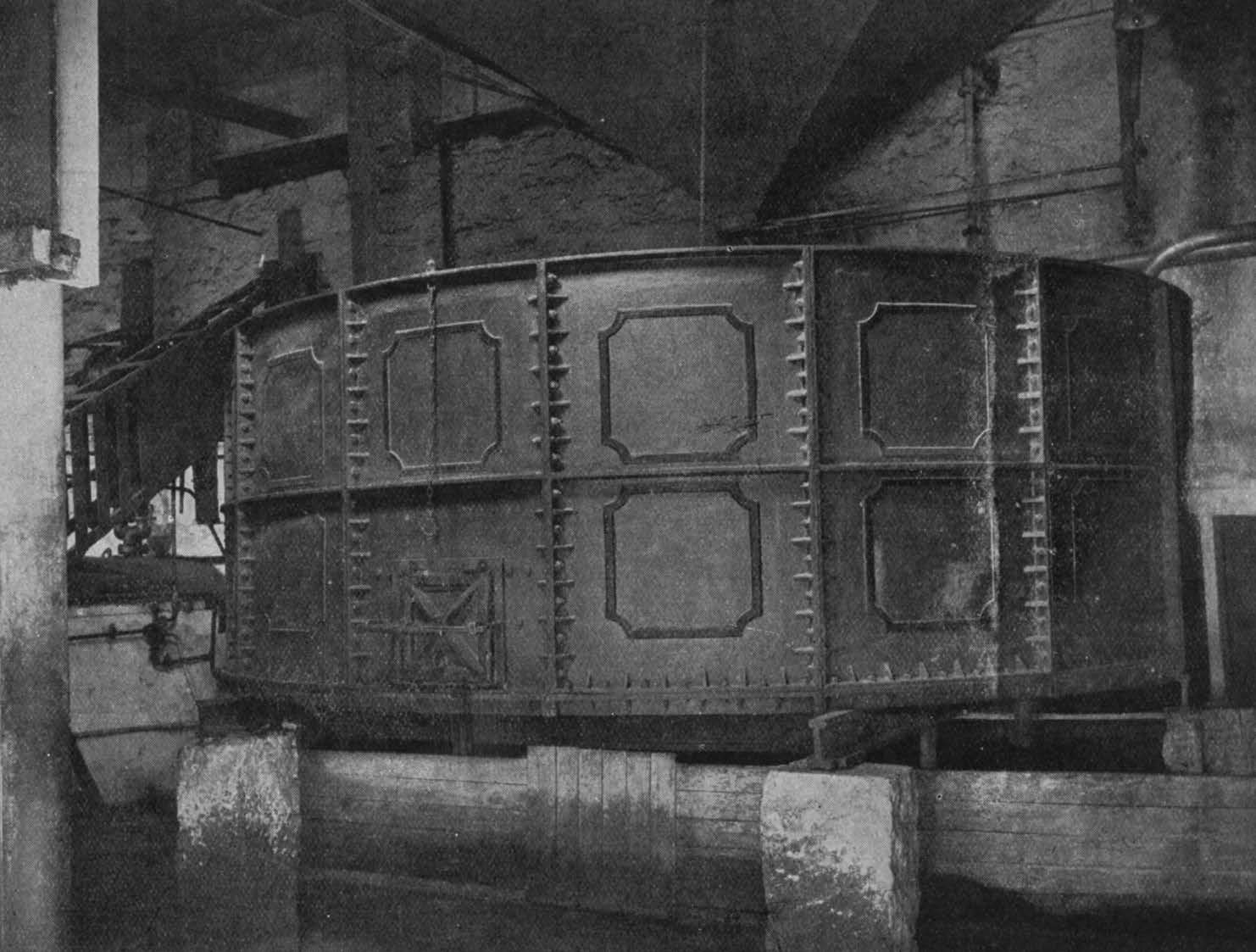

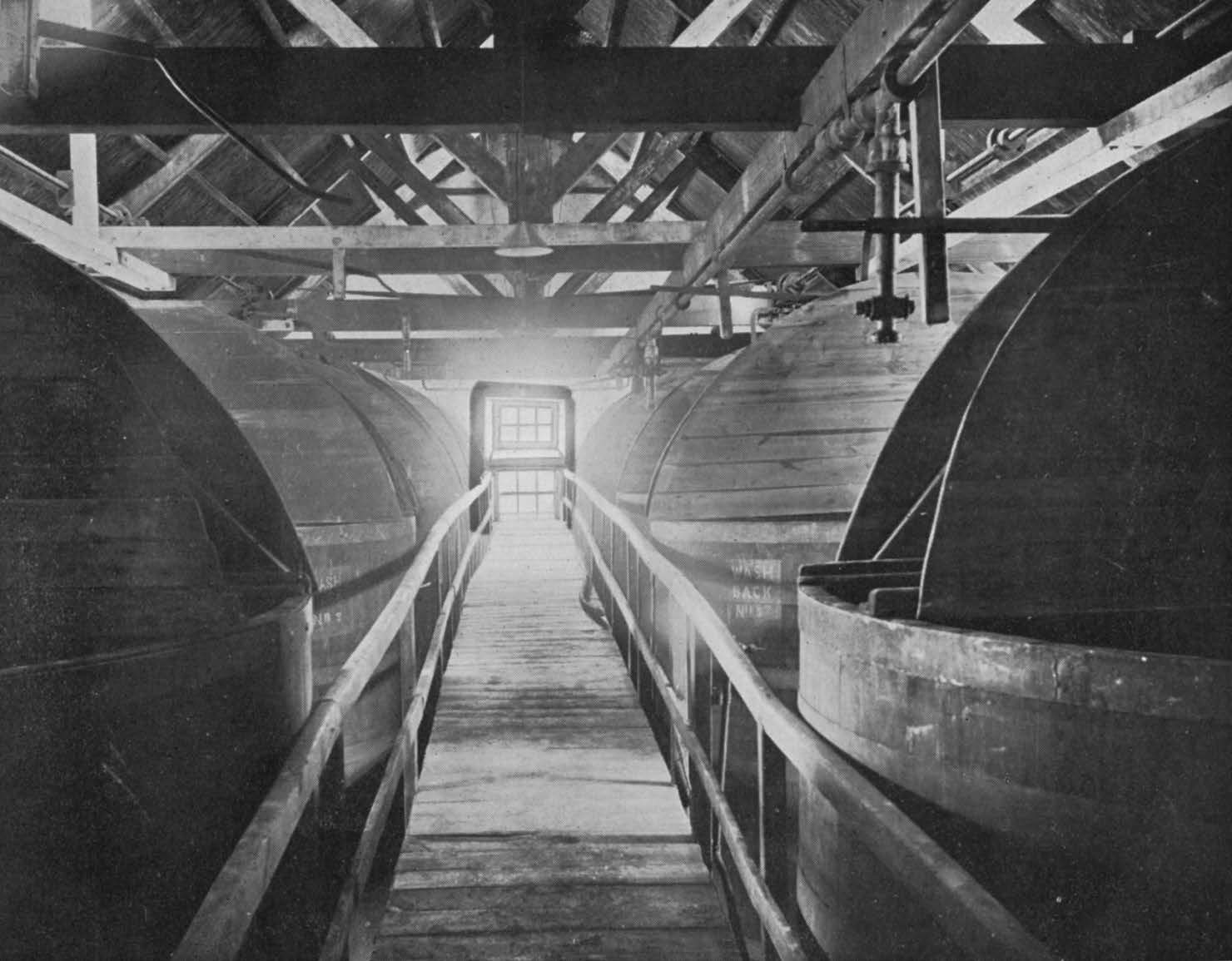

Two thousand bushels of malt are mashed, and ten backs afford space for fermentation of wash. The wash-still, which has been in use for 50 years, is of 4,000 gallons’ capacity, and the Spirit still can hold 2,680 gallons. Warehousing accommodation is extensive, the capacity of the bonds being equal to ten thousand butts. In the Spirit store, containing a vat of 2,015 gallons’ content, it is interesting to see one of the original “balance” weighing scales, a type of instrument said to be more in favour with the Excise authorities than the modern pattern. Power is provided by a 30-h.p. Tangye steam engine, and a splendid draff-drying plant is maintained. All the distillery buildings, bonds, managers’ and officers’ houses are supplied with electric light.

The disposition of burnt Ale has been solved in a novel manner, it being pumped from the distillery into the Moray Firth, four miles distant, through a pipe-line which cuts right through the intervening farms, the farmers – by the way – having the right to draw supplies from stopcocks placed on their respective farms.

Images © The British Library Board