CXXIV

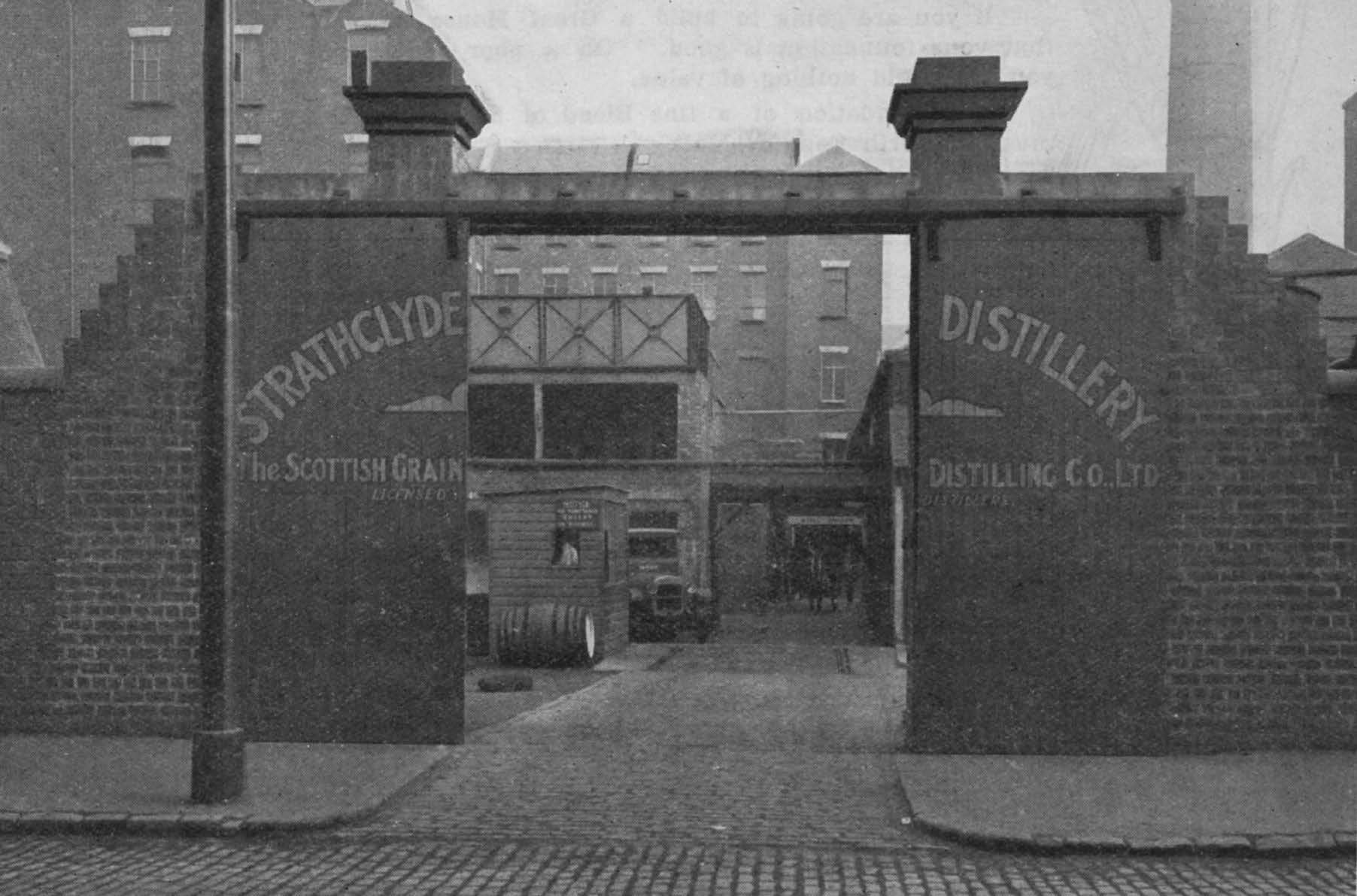

Strathclyde Distillery, Glasgow

October 14th, 1929

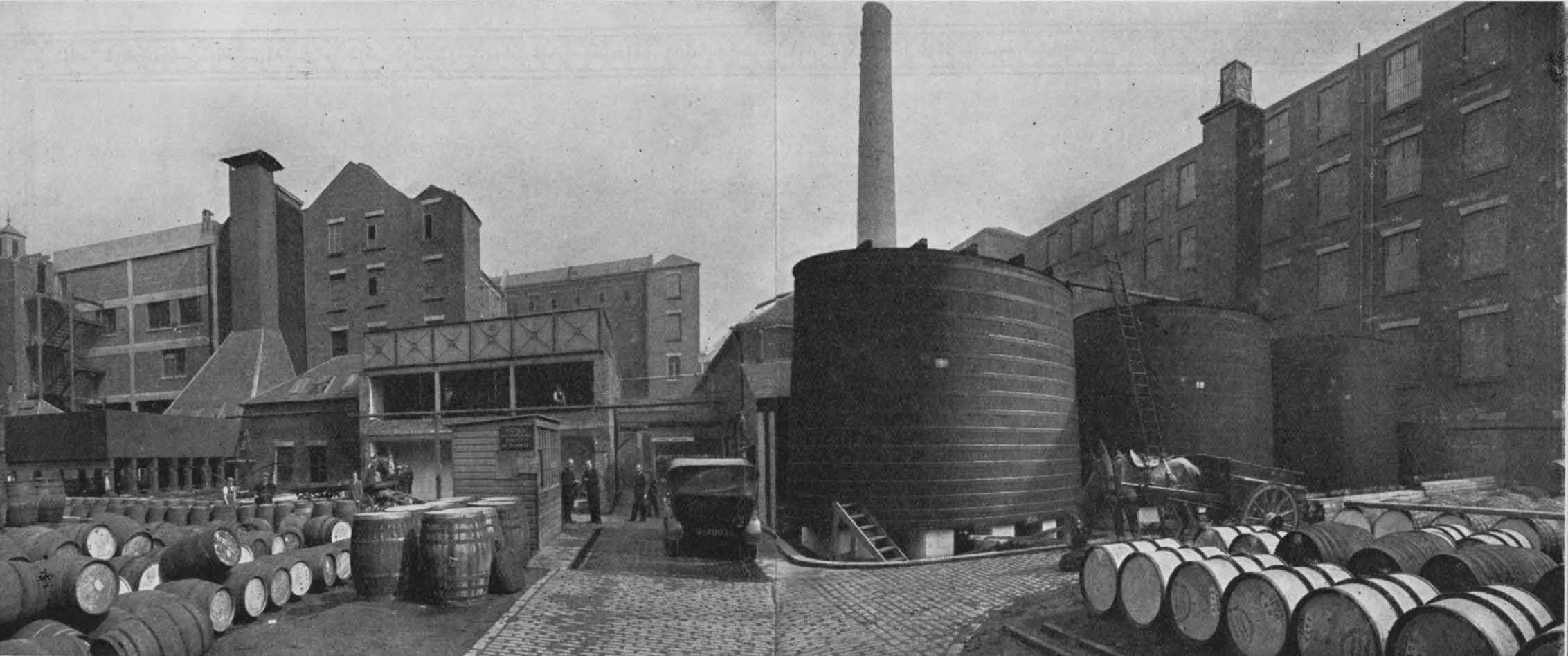

Although Strathclyde Distillery is of comparatively recent formation and has therefore no history in the sense of striking incidents, legends, biographical anecdotes, etc., it has yet created history in a very important sense. It must be admitted, in these days, when high Spirit duties are still in force, and when some other distilleries of even very ancient origin are conspicuously “silent,” it is surely something of a bold step to conceive the starting of an absolutely new distillery, and in this way, therefore, history may be said to be created when a distillery of the size and importance of Strathclyde can be successfully established in face of very apparent adverse factors.

ITS INAUGURATION.

As will probably be remembered by many, the formal inauguration of the distillery took place last year, and it has the great distinction of being the only Scotch grain distillery erected in Scotland during the last 20 years. After about 18 months of careful and painstaking preparation the distillery began working in September, 1928; consequently, since the commencement of operations there have been fifty-two working weeks, and on reaching the end of such a successful distillation period, the event is, we think, a very fitting occasion on which to pay a brief visit to the distillery.

Strathclyde Distillery is the property of the Scottish Grain Distilling Co., Ltd., a company registered in 1928. The distillery itself is situated in Govan Street, in the south side of Glasgow, and close to the River Clyde.

A MODEL GRAIN DISTILLERY.

When the idea of this new distillery was first mooted various experts were, of course, consulted, with a view to incorporating every possible improvement in its design, so that, when completed, Strathclyde could justly claim to be a model distillery of its kind. It incorporates improvements in plant that were not available when the other and older distilleries were erected. Whilst steam has perforce to be used, as in other similar concerns, for the actual technical process of distillation, electricity is employed for everything else, and consequently the entire establishment is run on the most hygienic principles.

DISTILLATION: WHAT IT IS.

We spoke a moment or two ago of distillation, and it may be helpful at this point to incorporate here the substance of a recent definition whereby we are informed distillation may be described as a process by which, when heat is applied, substances can be driven off, or, as it is technically termed, volatilised one from the other and recollected by condensation. A solvent, such as water, can thus be separated from any solids it holds in suspense. In the case of spirituous liquors, the first thing aimed at in distillation is the freeing, as much as practicable, of the alcohol from the non-volatile elements of the wash. Naturally, other volatile elements, for instance, water, and products of fermentation other than ethyl alcohol are distilled off. The proportion of these, however, is lessened by additional distillation and by different modifications of the still. Such modifications vary according to the materials (grain, or whatever else) that is used and the kind of Spirit required.

THE STRATHCLYDE PROCESS.

At Strathclyde Distillery a patent improved still is employed. In reality, it is a double still consisting of two adjacent columns termed respectively rectifier and analyser. But we are anticipating matters, and must return, as it were, to the beginning, or rather to the entrance to the vast establishment where, after passing through the well-appointed offices, we are shown the grain intake.

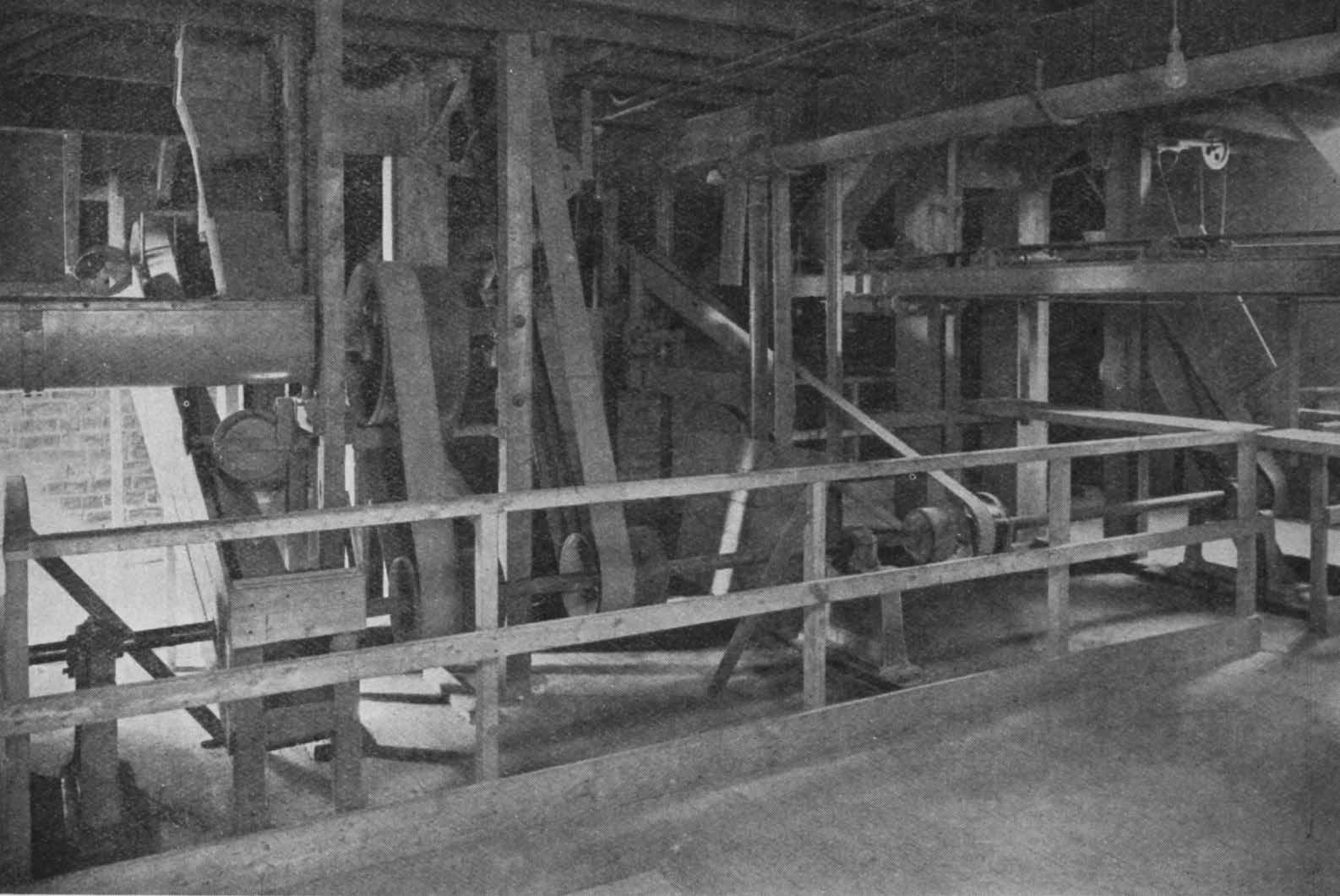

THE GRAIN INTAKE.

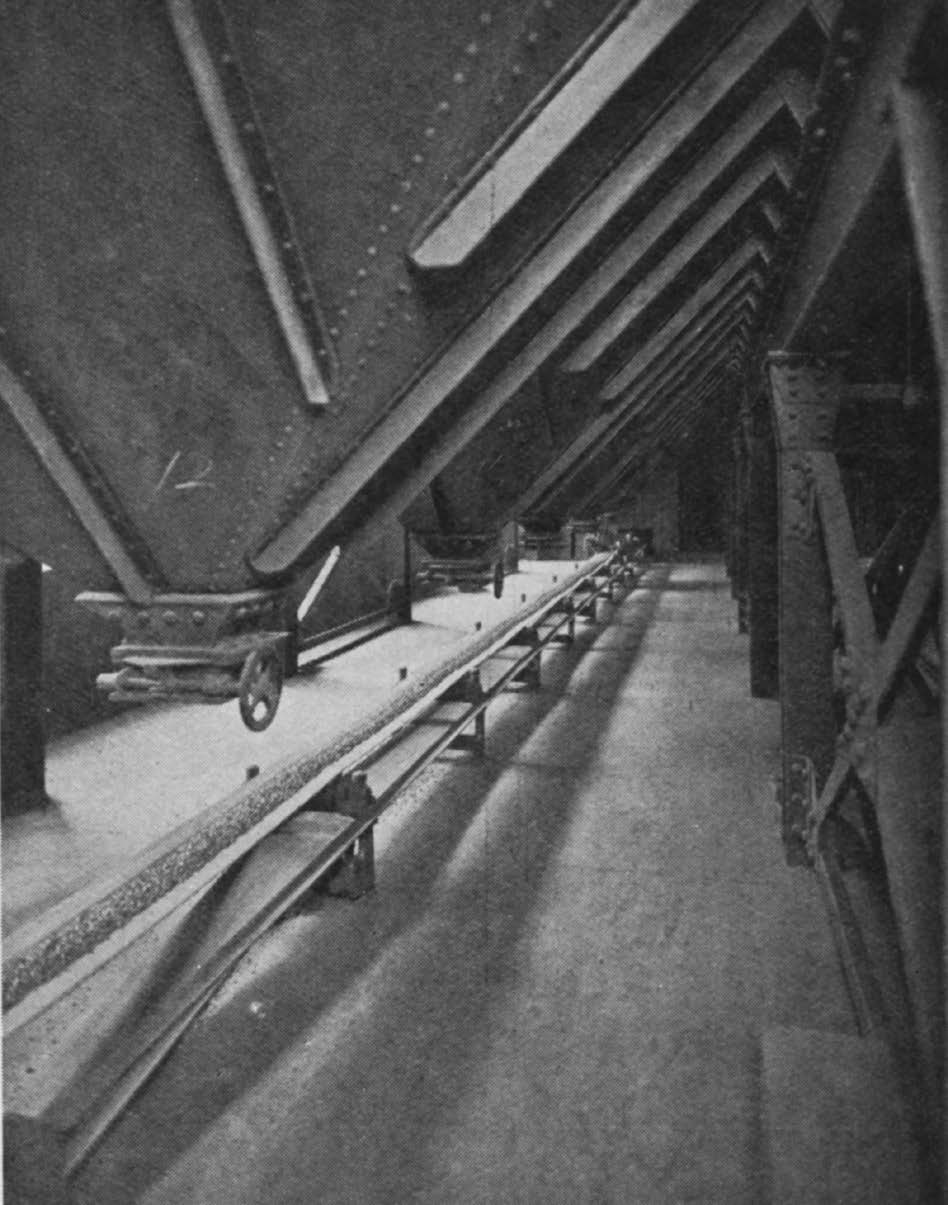

The grain, on its arrival, is taken from the carts to the automatic weighing machines and thence by an elevator to the band conveyor. From the band conveyor it is discharged into the grain hoppers. Before the grain is put into the bins it passes over cleaning machinery. A system of elevators and grain conveyors brings the grain to the mill hoppers. From the mills the grain is deposited in the grist hoppers. It is then conveyed through automatic weighing machines to the different mashing processes.

MASHING.

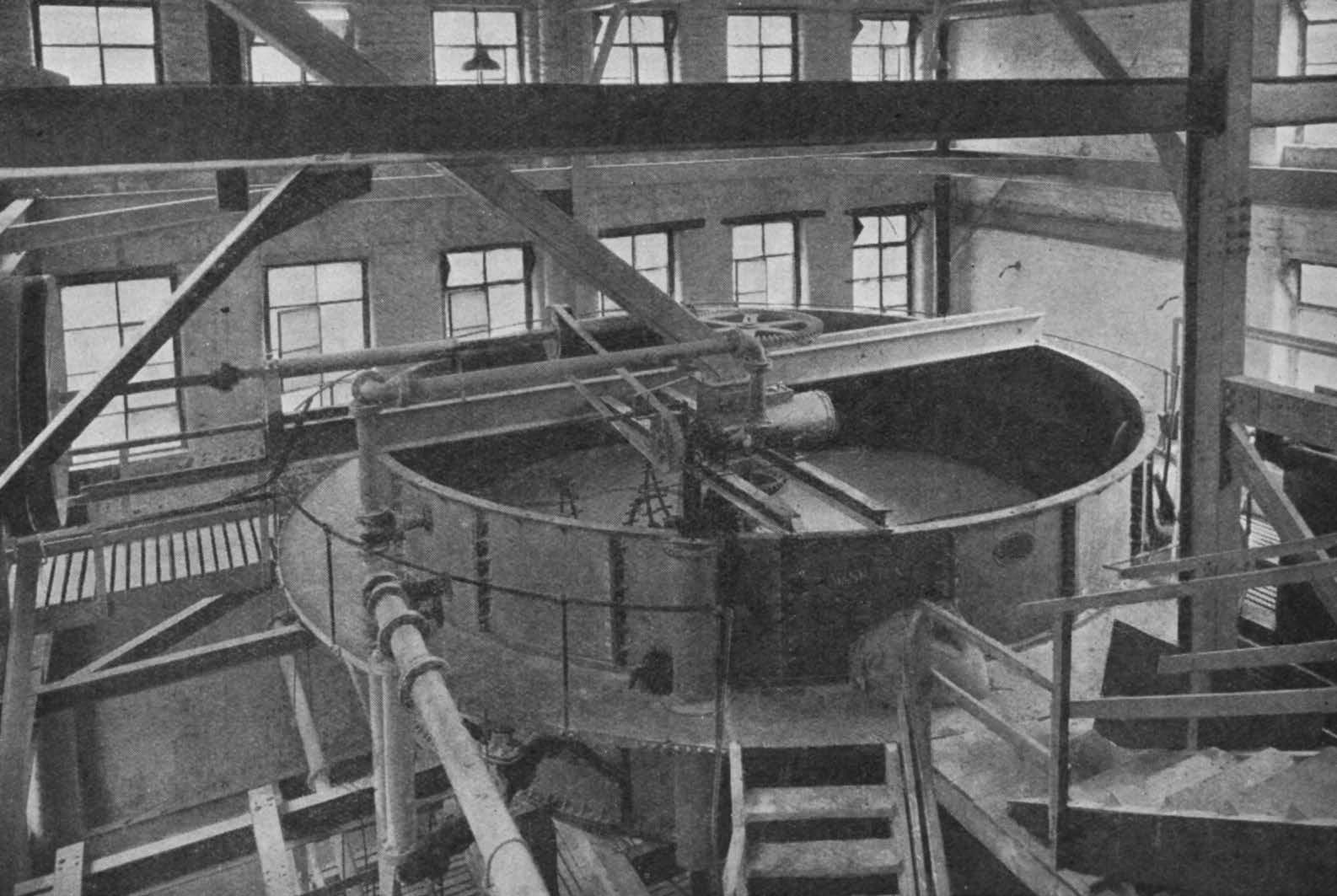

The mashing process consists in boiling of the maize, the mixing of malt, and other grains which are used for mashing, with attemperated water and the mixture of grain and water come together in the mash tun.

In the mash tun, which is situated at a very high level, and the fixing of which called for much engineering skill, the starch contained in the different ingredients is converted into sugar and rendered suitable for fermentation.

The mash tun is fitted with stirring gear, and has a double bottom with perforations. The contents of the mash tun is drawn off at the bottom – as everything possible goes by gravitation – and conveyed to a collecting back, the grain residue remaining in the mash tun, to be subjected to a process of washing out.

FERMENTING.

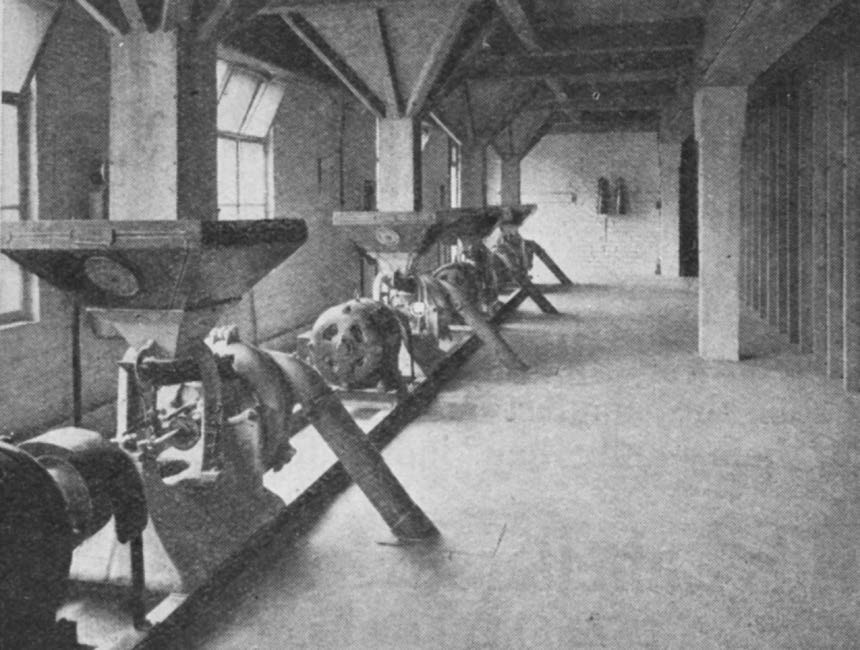

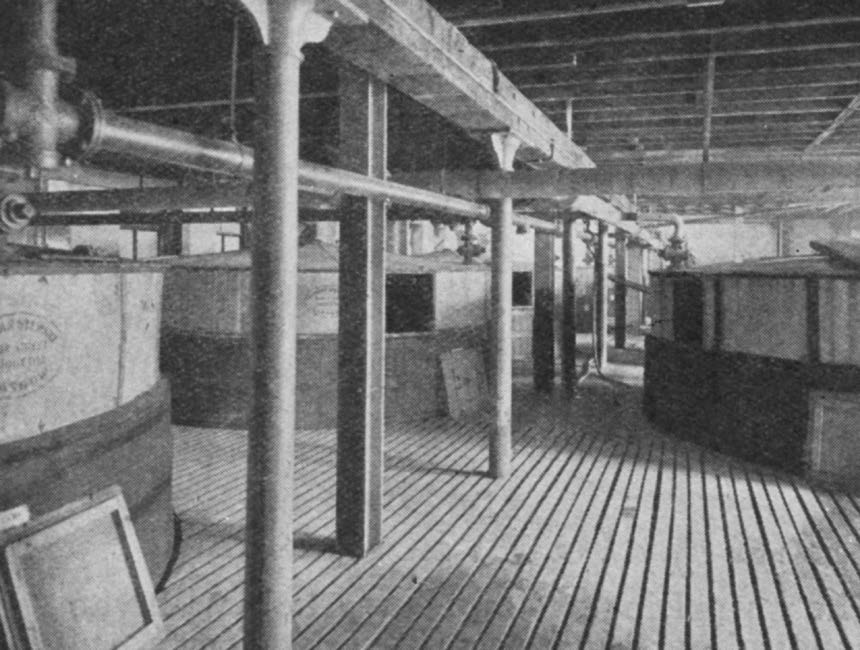

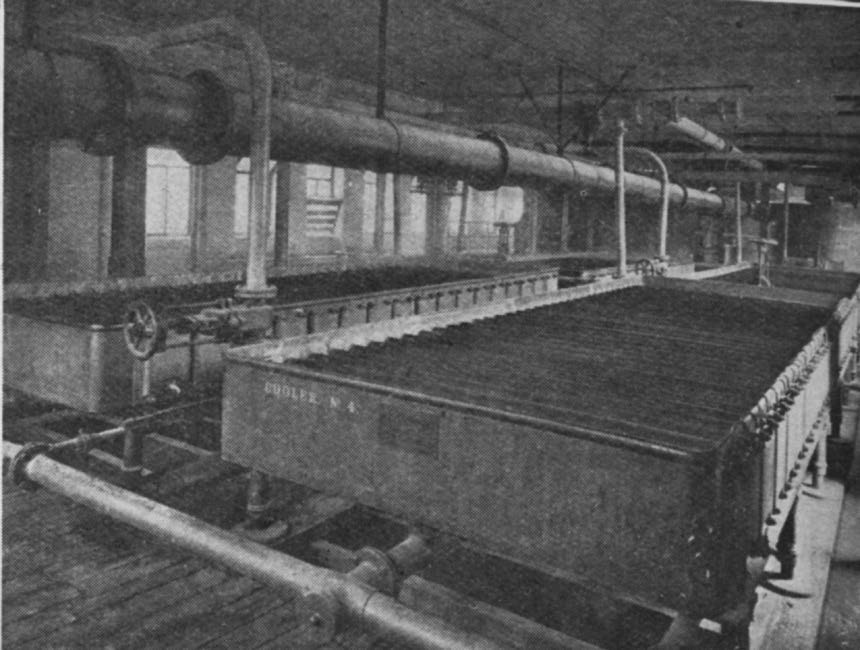

The main sugar solution, or main wort, and also the extract which is obtained by washing out the grain residue are collected after passing over coolers and the fermenting vats (washbacks) which, as can be seen from our illustration, are covered-in vessels. They are closed in for the purpose of collecting through the process of fermentation. The wash which has been collected in the fermenting vats is mixed with a small auxiliary mash. The process of fermentation is completed in from 48 to 60 hours, and after the fermentation has been completed the contents of the fermenting backs is transferred to measuring tanks, the object of which is to give the Excise officers an opportunity of estimating the alcohol which should be produced during the process of distillation to which the wort must now be subjected.

THE STILL HOUSE.

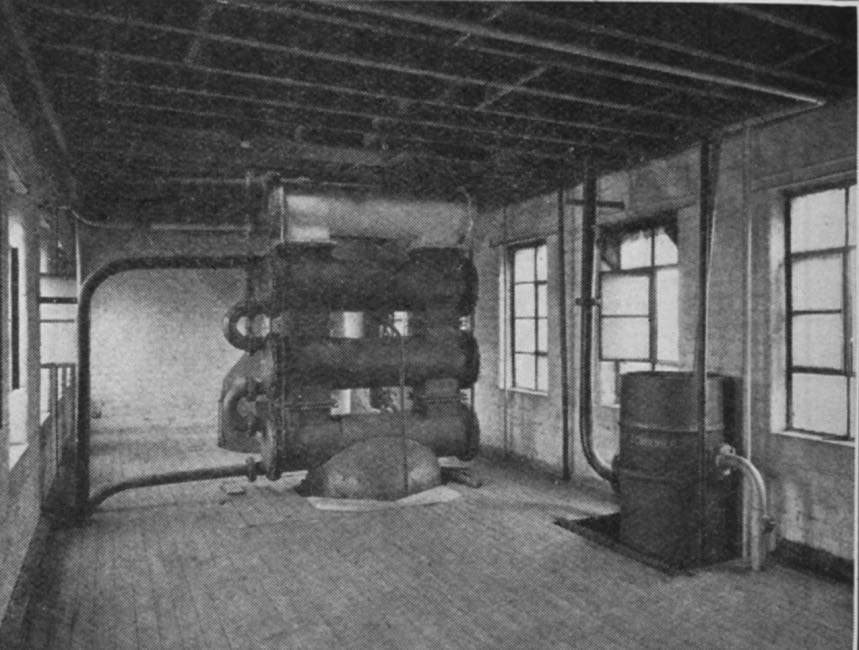

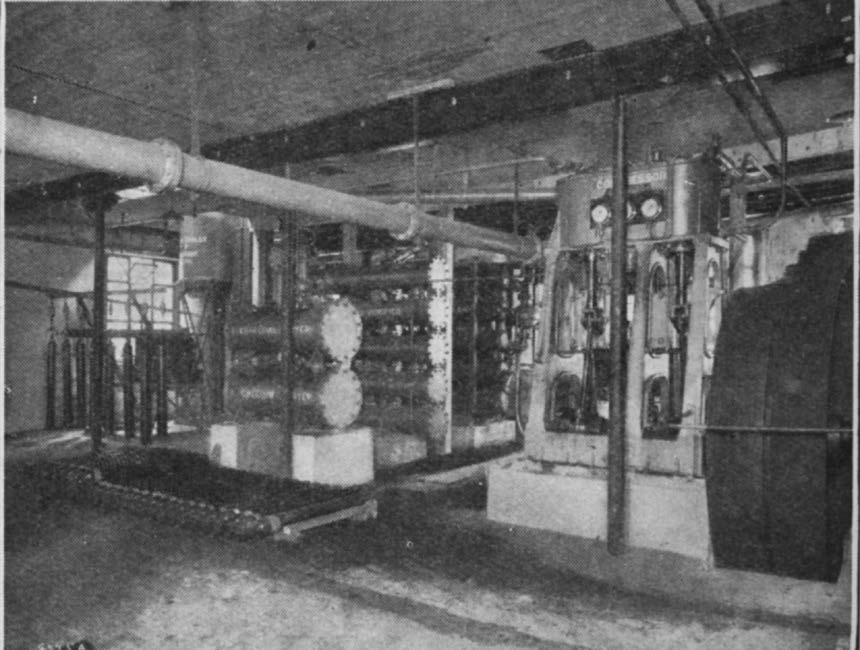

From the measuring tanks the fermented worts are pumped through a system of pre-heaters, named dephlegmator, to the analysing column in which the separation of the alcohol from the liquor takes place. The alcohol is driven off by steam, and the alcoholic vapours pass from the top of the analyser to the bottom of the rectifier column. The analyser and the rectifier have each a building height of 45 feet, which will give some idea of the size of the stills. It goes without saying that the progress of the fermentation is carefully followed up by testing from time to time, and every “shift” makes the necessary records.

CENTRALISATION OF CONTROLS.

For the control of the stills various instruments are necessary, such as pressure gauges for steam from the steam mains; pressure gauges to show the pressure inside the analyser and rectifier column; thermometers for ascertaining the temperature of the worts after it has passes through the dephlegmator and the pre-heater. There are also instruments for measuring the alcoholic contents of the vapour at the bottom of the rectifier and analyser column, to ensure that no alcohol is lost when discharging the affluent from the stills, and instruments for testing the Spirit, as it is produced, in respect of strength and quality.

All these instruments have been so arranged that one man can superintend them all from the one platform. This platform is shown in our illustration.

CONDENSING.

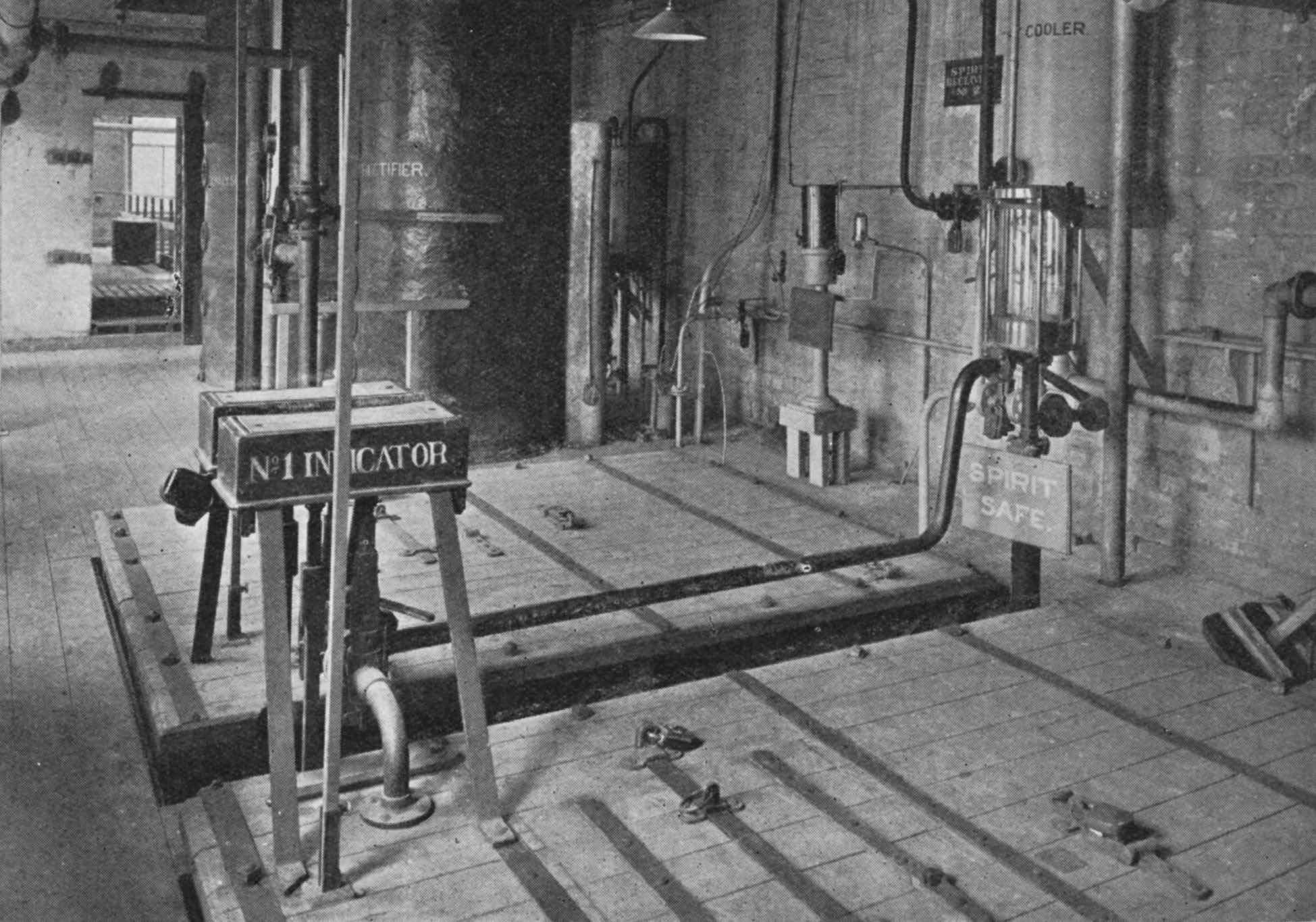

The Spirit is taken off by means of a pipe leading from the top of the rectifier to a condenser, whence it runs to the Spirit receivers.

All the spent wash that comes from the still passes through a vat. A steam pump pumps it to the spent wash vat, and the arrangement is such that the level is kept automatically the same. This arrangement does not require the use of any manual labour.

In order to protect the Excise revenue crown locks have, as is required by distillery law, been affixed to all parts where Spirit could possibly be extracted by unscrewing parts. A combination of iron bars and locks prevents any unauthorized loosening of joints.

The Spirit is measured in the Spirit receivers by the Inland Revenue officers, and this measurement must agree with the estimate previously calculated at the wash chargers.

THE SPIRIT STORE VATS.

From the Spirit receivers the Spirit runs by gravitation to the Spirit store vats, from which the Spirit is brought by dilution to the most suitable strength for trade purposes. It is then filled into casks preparatory to being warehoused.

The grain residue, during the winter, is sold in wet conditions to the farmers, as cattle food. During the summer it is dried and sold to cattle food manufacturers. The carbonic acid which is produced during fermentation is conveyed to the CO2 compressing department where, by means of electrically driven compressors it is liquefied and filled into steel containers ready to be sold to aërated water manufacturers, or to shipping companies who use the gas for refrigerating purposes on board ship.

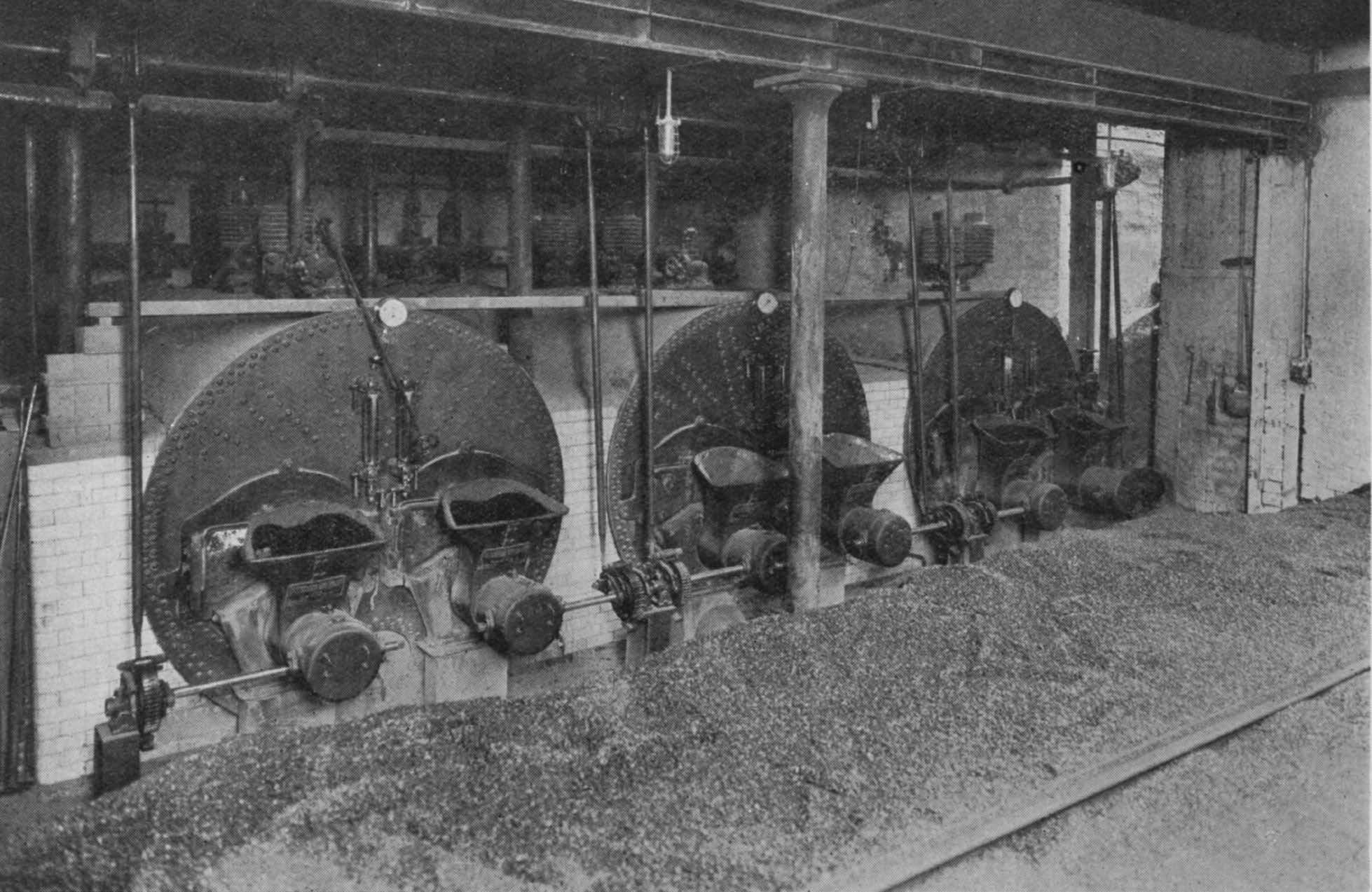

We have previously spoken of the necessary use of steam, and may here remark that steam is supplied, to the various departments in which it is required, from three Lancashire boilers, fitted with underfeed stokers in order to prevent, as much as possible, the formation of smoke.

THE AUXILIARY DEPARTMENTS.

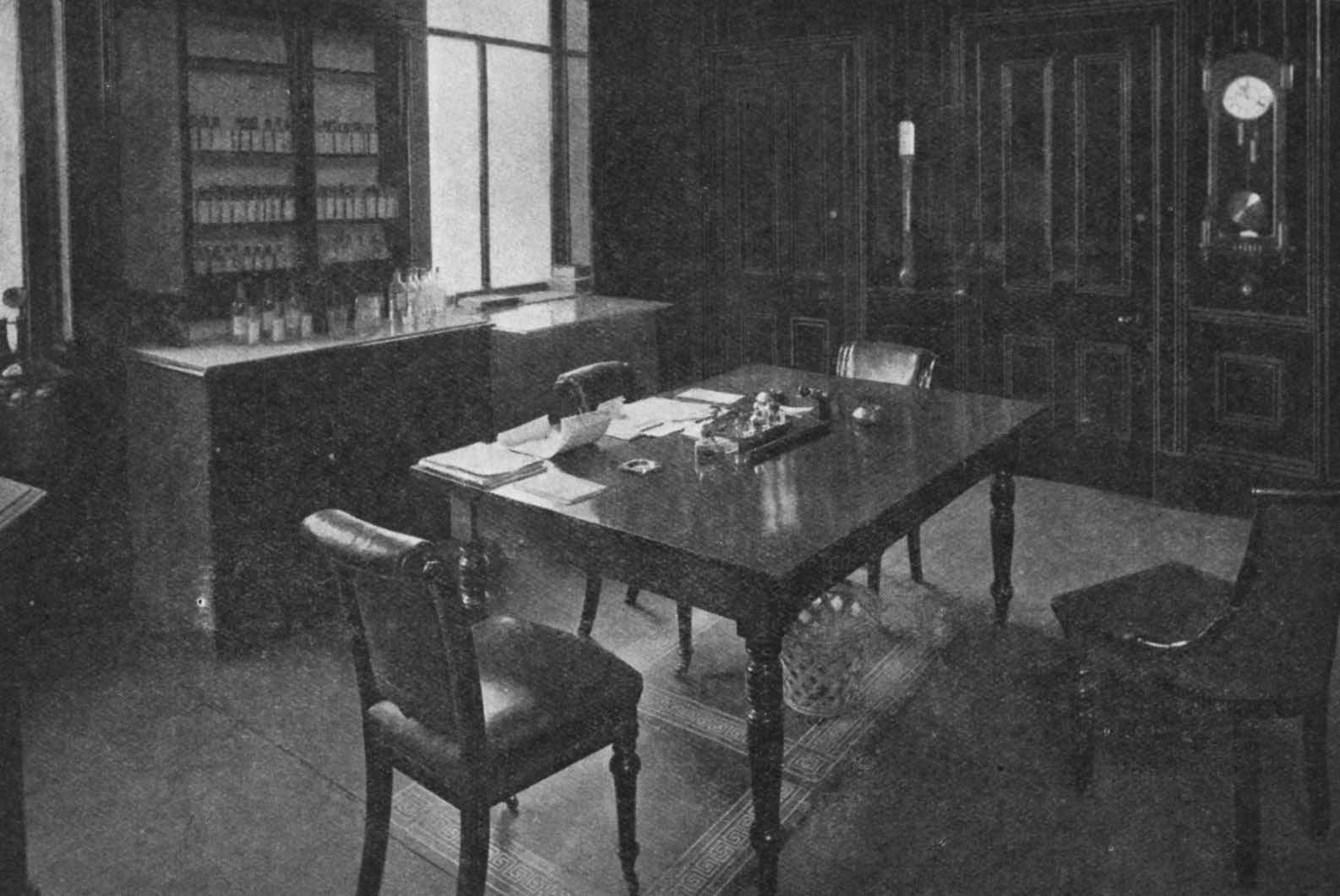

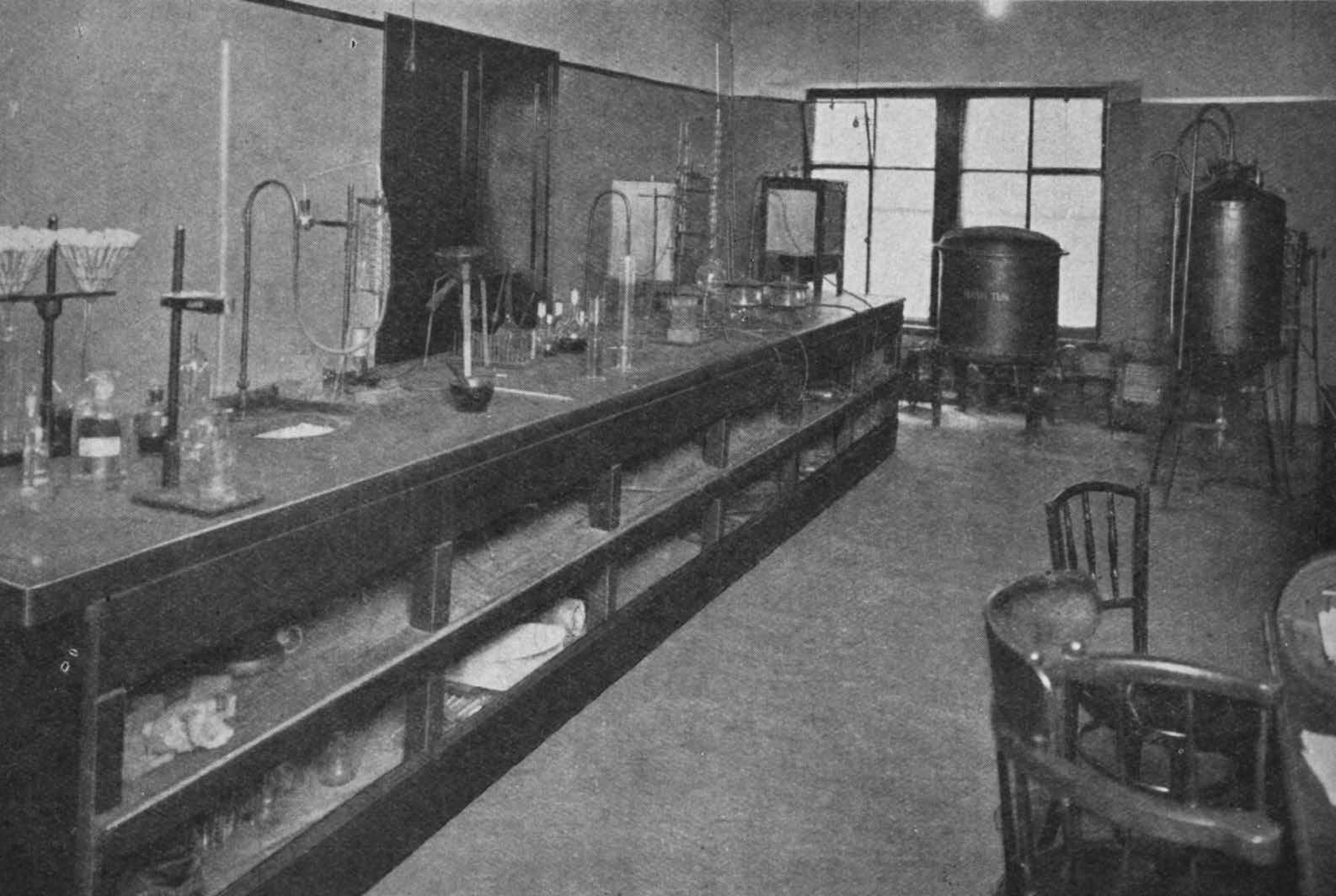

Needless to say in the case of such an up-to-date distillery, there is not only a brewer’s office, blacksmith’s shop, etc., etc., but more important than all a handsomely equipped laboratory, and, along with other indispensable work, it is here that a pure culture yeast is prepared, to be used ultimately for starting the fermentation in the fermenting vats.

Conveniently situated above the laboratory are the various rooms forming the offices for the Inland Revenue officials.

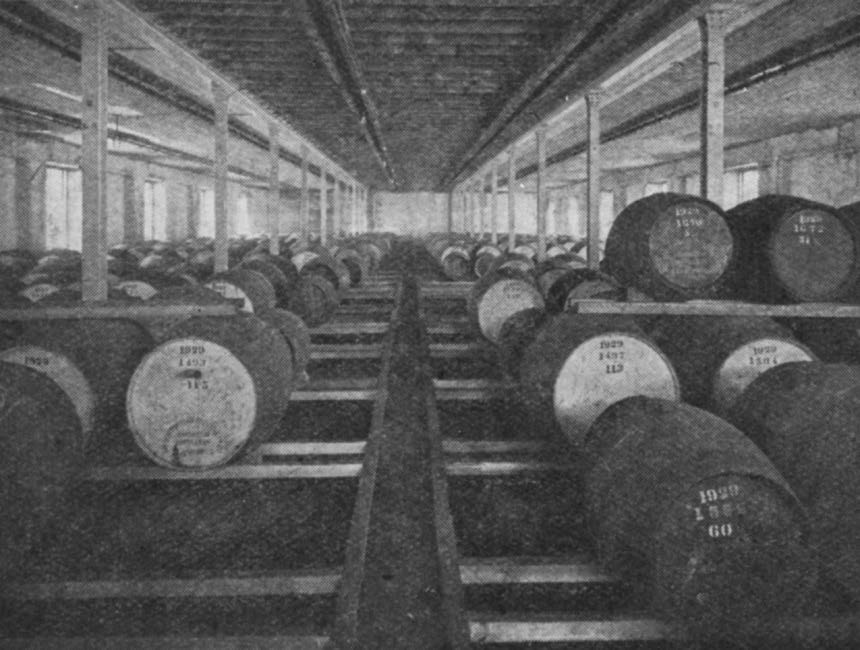

THE 1,000,000 GALLON BOND.

The Spirit, after leaving the Spirit still and being put in barrels, is brought to a bonded warehouse, built close to the main establishment. This bonded warehouse is a building in which approximately 1,000,000 gallons of Spirit can be adequately stored. This large store capacity is necessitated by reason of the fact that all Whisky, before going into consumption, must have passed through a period of maturation of not less than three years.

HYGIENIC PRECAUTIONS FOR PURITY OF PRODUCT.

Altogether, speaking from an experience based on visits to very many distilleries – including some of the largest and finest in the world – we were greatly impressed by the high standard of cleanliness existing throughout the various departments – the careful attention to hygiene being largely brought about by the aid of the electrical appliances adopted on the advice of the distillery designers – the scrupulous observance of well-drawn-up rules and regulations, so that the slightest hitch anywhere in the proceedings was rectified with the minimum amount of delay, and, finally, by the evident wholesomeness and absolute purity of the product. A factor of considerable importance in attaining such excellence is that the company have access to an ample supply of Loch Katrine water, than which it is said there is no finer in the world for distilling purposes. Moreover, the company have the advantage of a special rate for the supply of this water – a rate that was granted to the previous owners by the Glasgow Corporation in return for the surrender of certain rights enjoyed by them.

STRATHCLYDE AN OUTSTANDING SPIRIT.

In these difficult days in which to establish new businesses, it is pleasant to reflect that from the outset the Spirit produced at Strathclyde turned out to be of the finest quality; a quality which has been, and we are fully assured, will be rigorously maintained. As a matter of fact, quite early in the initial stages the Spirit was submitted to a searching analysis, together with a sample of Spirit obtained from another leading distillery, and the report proved that Strathclyde is what the promoters set out to make it – namely, an altogether outstanding Spirit.

This fine result speaks volumes for the technological knowledge and ability of the general manager, Mr. C. W. Moeth, who was the technical pioneer of the project from the very commencement.

As far as can be forecasted at the present time – the distillery products have yet two years to run to reach the prescribed minimum maturity – the venture is going to be a success, and even at the moment of writing has not only proved itself to be a workable proposition, but a welcome and beneficial addition to an old and important section of the trade.

Images © The British Library Board